Summary: The amazing conclusion of the story of Tischendorf’s life and his discovery of the world’s oldest Bible. Part 2 of a 2-part series.

I rejoice at thy word, as one that findeth great spoil. – Psalm 119:162 (KJV)

The Search for the Most Ancient Biblical Texts

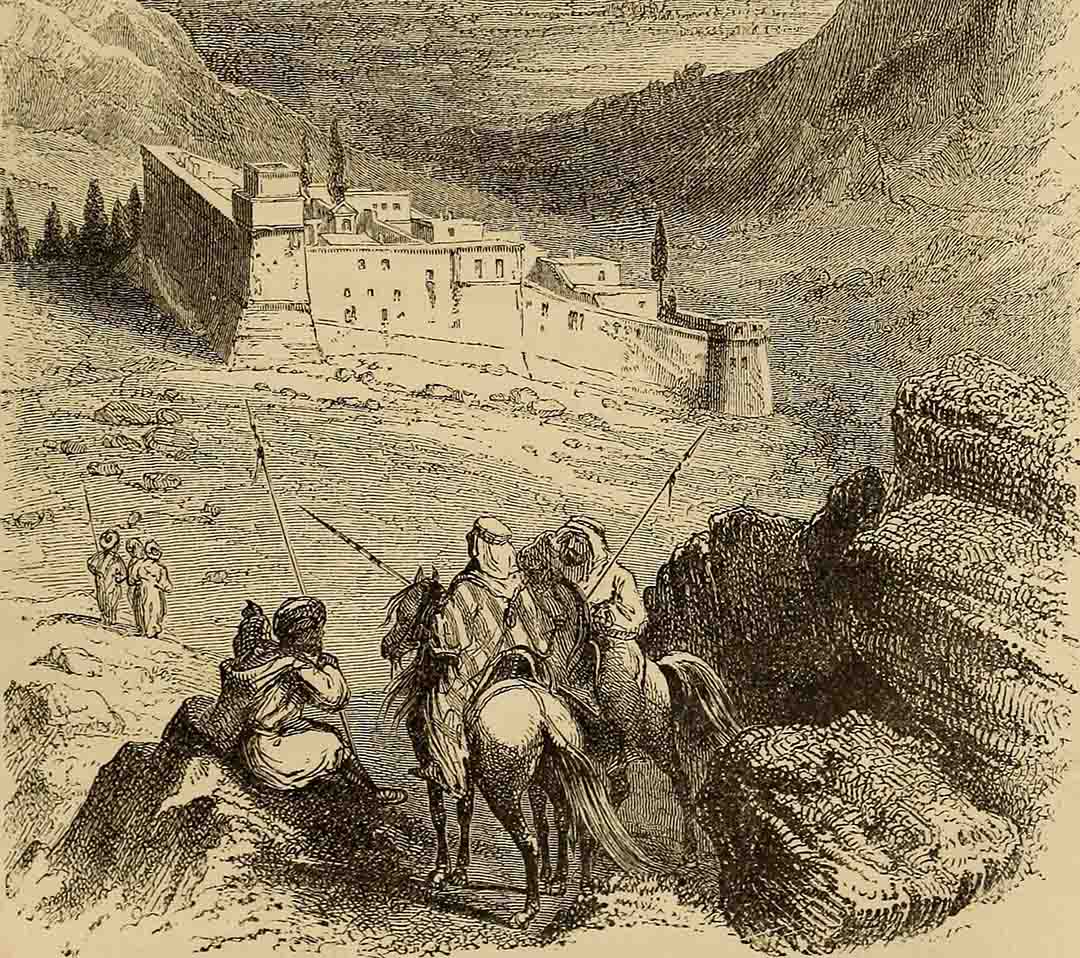

In his search for the most ancient texts of the Bible, Constantin Tischendorf most wanted to visit St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai. Of all the libraries in the Middle East, St. Catherine’s library was the oldest and most famous.

After two weeks of dangerous desert travel, the Saxon Bible student reached the secluded convent in the south of the Sinai with a small camel caravan in May of 1844.

But the tribulations would be worth it! In the monastery he discovered 129 sheets of the ancient Bible which is now world-famous as the Codex Sinaiticus (Book from Sinai). Tischendorf accepted 43 sheets as a gift from the Sinai monks and brought them to Leipzig. He left the others behind and asked the monks to look out for further sheets.

The return journey went by way of Suez to Cairo, and then on to Jerusalem, Shechem, Beirut, Smyrna, Patmos, Constantinople, and Athens. He visited the libraries everywhere he went. He then went back to Lengenfeld through Italy, Vienna, and Munich at Christmas of 1844. A few days later, he went to see his Angelika. He became engaged at that time, and they married in 1845.

Upon his return, he was appointed professor at the University of Leipzig, where he immediately published the leaves from the Old Testament in an exemplary edition, but without revealing the site of their discovery. In 1853, Tischendorf traveled to the Middle East a second time to find the rest of the manuscript. But he discovered only a small fragment.

In January 1859, a third trip to the Middle East followed. He wrote to his wife Angelika, “I go in the name of the Lord, looking for treasures that will bear fruit for His church.” For this third trip, Tischendorf even inspired the house of the Czar. Czar Alexander II was the patron saint of the Greek Orthodox Church. He took over the travel expenses, and the Czar’s brother, Grand Duke Constantine, became Tischendorf’s most important patron.

The monks in the monastery already knew Tischendorf well, but no one could remember what had become of the 86 sheets that had been left behind from the Bible discovery in 1844.

The Discovery of the complete Codex Sinaiticus

Once more, Tischendorf combed through the rooms in which the library was housed with its thousands of books. But to no avail! Shortly before leaving, he ascended the traditional Mount Sinai, and as he was refreshed by a monk upon his return, he was shown “his” Greek Bible. It was February 4, 1859, a date that has gone down in Bible history!

The monk brought Tischendorf a thick parchment bundle that was wrapped in a red cloth. This bundle contained not just the 86 left-behind sheets, but more leaves from the Old Testament and the entire New Testament! Tischendorf had reached his desired goal.

To his wife he wrote, “I had hoped to give a victory bulletin: now truly, the Lord has decreed that it would be one. He has already given such a great blessing to my research in its first steps that I had only tears of emotion in response…What gave me no peace at home, so much that it also leaned on human striving and longings, that was the call of the Lord. I had always said it: I go in the name of the Lord and search for treasures that will bear fruit for His church: now I know it, and I was honestly shocked by the truth myself. The entire manuscript, as it is now, is an incomparable gem for science and the church” (Cairo, 15 February 1859).

The Influence of the Codex Sinaiticus

A purchase of the manuscript was impossible, but the monks liked the idea of a gift to the Russian Czar. However, this was not carried out immediately, as the former Archbishop of the Sinai had just died, and a new one had to first be selected and accepted. As long as the gift was not immediately possible, Tischendorf’s manuscript would be given for publication purposes against a certificate of guarantee from the Russian ambassador. Czar Alexander II was delighted by the discovery and took over the costs of publishing a facsimile (detailed replica).

The University of Leipzig established a Chair of “Biblical Paleography and Theology” just for Tischendorf. In an incredibly short period of three years—Tischendorf must have toiled day and night—he accomplished the Herculean task.

In 1862, the Codex Sinaiticus appeared as a magnificent reprint for the Russian Czar, for the 1000-year anniversary of the Russian Empire. The Czar gave the facsimile away to all the major libraries and royal dynasties.

In addition to this, Tischendorf also published inexpensive editions and various publications on the history of the discovery of the “Sinai Bible,” as the Codex was then called.

Tischendorf also revised his text edition of the New Testament again. As already mentioned, Tischendorf released 24 editions of the New Testament in Greek during his life as a researcher.

The highlight is the “Editio Octava Critica Maior,” (Volume I 1869 / Volume II 1872), which is considered a milestone and is still used in New Testament textual research today. This edition of the Codex Sinaiticus takes the most important position next to the Codex Vaticanus as a textual witness.

Many questions of textual criticism could be resolved, and at the same time it pointed out that the New Testament has been quite outstandingly passed down. To date, the discovery of the Sinaiticus from the 4th century leaves all other discoveries in the shadows. Meanwhile, there are certainly older records of the New Testament, but only the Sinaiticus offers the entire New Testament!

The Transfer of the Codex Sinaiticus

The monks gave the valuable manuscript in 1869 as a gift to the Czar, after which the monastery received 9,000 rubles in return, as is customary in the Middle East.

Tischendorf’s discovery of the manuscript has often been described. Shortly before his death (1874), however, there were voices alleging that Tischendorf had fraudulently taken the Sinaitic manuscript. It is often said that he had the manuscript only on loan, but it was never returned in spite of promises made; instead, that he bequeathed it to the Czar without permission from the monks.

Within the scope of the digital research project, archives were searched intensely in Germany, England, and especially in Russia and in Saint Catherine’s Monastery—with great success! The monks’ deed of a gift to the Russian Emperor was found in the Czar’s archive. Professor Christfried Böttrich of the University of Greifswald (formerly Leipzig) has published, among other things, these documents in German as part of the digital research project.

I can only support his conclusion: “The transfer of ‘Codex Sinaiticus’ to St. Petersburg took place—despite…all the difficult circumstances—legally correctly. A theft is, in any case, out of the question.”

For over two decades I’ve researched Tischendorf. His descendants have given me his estate to process (among other things, 300 love letters from 1838-1868, with more than 1,000 pages). For years I also worked with unpublished scientific works, which are preserved at the University of Leipzig. From all of the documents, it is doubtless that Tischendorf was not only a devout Christian, but also a gentleman all the way!

For his 200th birthday anniversary, the city of Lengenfeld (near Dresden) held a large Bible and Tischendorf exhibition at City Hall. The accompanying anniversary lectures and church services were very well attended. Tischendorf’s great-granddaughter traveled specially from London for the occasion, and approximately 3,000 visitors flocked from all over Germany to tiny Lengenfeld.

It is a pleasure to see how this unique biblical scholar and his scholarship have newly aroused the interest of the people, because his research adventures are more exciting than any thriller.

Tischendorf’s motto was, “Doubtless, science strengthens the research, but only faith sanctifies it!” Therefore, he had always tried to explain all of his research to the Christian community and make it accessible.

Unfortunately, Tischendorf’s fascinating life and work are wholly unknown to many Christians today. It is very welcome that an effort is being made to rename the city of his birth “Tischendorfstadt-Lengenfeld.”

Tischendorf once said, “You know that it was enthusiasm for the Book of books that swept me from the arms of friends and saw me under foreign skies, looking for hidden treasures” (“Letter from Jerusalem,” 15 July 1844).

Tischendorf found Bible treasures in quantity, and through him, modern textual research was founded. Additional discoveries of the New Testament in the hot desert sands of Egypt in the 1930s and 50s demonstrate the outstanding tradition of the New Testament writings.

Conclusion

Despite all predictions to the contrary, the New Testament is well documented. No text in antiquity can boast such a wealth of tradition. God watches over His Word!

Tischendorf’s manuscripts are a milestone in textual research, and equal in meaning to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Today, Tischendorf’s findings decorate the greatest museums in the world. Among all of his discoveries, the Codex Sinaiticus stands out. Through him we have a copy of the entire New Testament from the 4th century in front of us!

In John 20:31, we read the reason for the writing of the Gospels: “But these are written, that ye might believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God; and that believing ye might have life through his name.”

If we personally accept Jesus in our life as the Messiah, the Savior and Redeemer of the world, then the Bible will be a very personal book for us. And may Psalm 119:162 be as true in our lives as it was for Bible researcher Tischendorf: “I rejoice at thy word, as one that findeth great spoil.” – Alexander Schick

Keep Thinking!

TOP PHOTO: The convent of St. Catharine on Mount Sinai, Christianity’s oldest, continuously-inhabited monastery. (credit: Internet Archive Book Images, no restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons)

NOTE: Not every view expressed by scholars contributing Thinker articles necessarily reflects the views of Patterns of Evidence. We include perspectives from various sides of debates on biblical matters so that readers can become familiar with the different arguments involved. – Keep Thinking!