Summary: The tearing of the Temple curtain when Jesus died holds positive meaning for Christians, the opening of access to God and his forgiveness through Jesus’ atoning death. But there is more significance to the sign than many realize.

It was now about the sixth hour, and there was darkness over the whole land until the ninth hour, while the sun’s light failed. And the curtain of the temple was torn in two. – Luke 23:44-45 (ESV)

The Rending of the Temple Curtain at the Death of Jesus

Each Good Friday Christians remember the death of Jesus, with the accompanying darkness, earthquake, the rending of the Temple curtain from top to bottom, and more (Matthew 27:51-53; Mark 15:33-38; Luke 23:44-45). The darkness cannot have been a solar eclipse, because the full Passover moon is always on the wrong side of the earth for that to be possible. The darkness may have come from a khamsin dust storm. Both the darkness and the earthquake were widespread. The tearing of the curtain was localized at the holiest place on earth.

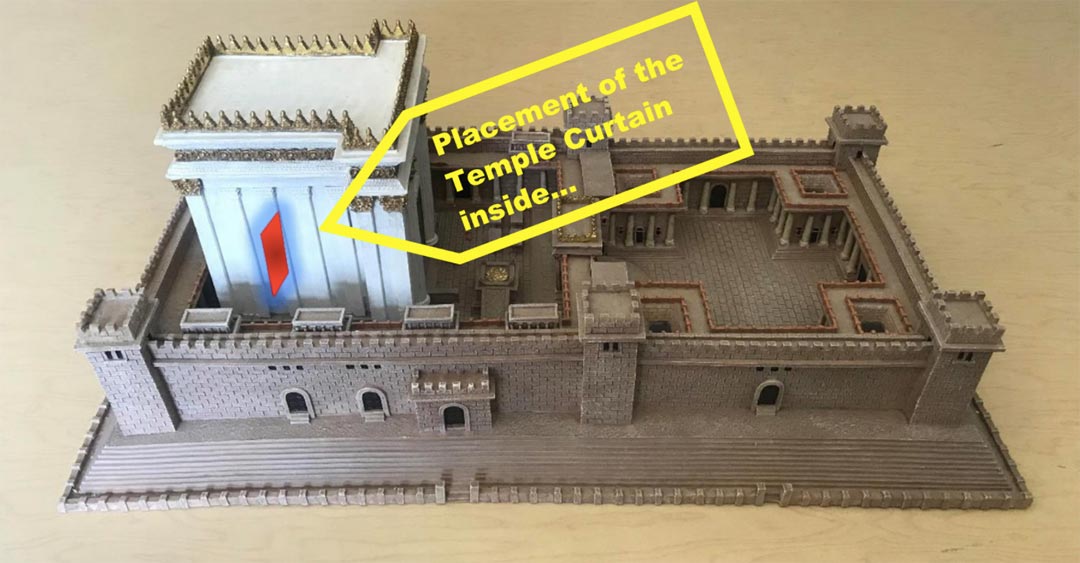

New Testament scholars point out that there were curtains in numerous places (18) in the Temple. But the Gospels surely mean the curtain most notable, most impressive, and most significant of them all. This was the curtain that separated the holiest place within the Temple proper (the naos) from the rest of the naos, and the surrounding structures of the Temple precincts. For it to be seen, the 30-foot–tall naos doors would have to be open, as we might expect them to be when the Passover lambs were being slaughtered in front of them, and the court of Israel was filled with men in three consecutive waves. These Israelites would have been able to look up and see that the Temple curtain toward the back of the naos had been torn.

And behold, the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom. And the earth shook, and the rocks were split. – Matthew 27:51 (ESV)

The Magnificent Temple Tapestry

The curtain contributed to the splendor of the Temple. From Josephus and rabbinic texts we can gain some idea of its appearance. Within that central structure of the Temple, the curtain covered the entrance to the Holy of Holies which was 40 by 20 cubits, or 60’ high by 30’ feet wide.

The curtain is described in Mishnah Shekalim 8:3. (The Mishnah is the oral tradition of Jewish Law, first put in writing about the end of the Second Century AD. It is the foundation of the Talmud.) Some interpret this to mean the curtain had 72 squares joined together. Perhaps the tear happened at the central seam.

Josephus, who had seen the curtain, wrote:

“It was a Babylonian curtain, embroidered with blue, and fine linen, and scarlet, and purple, and of a contexture that was truly wonderful. Nor was this mixture of colors without its mystical interpretation, but was a kind of image of the universe; for by the scarlet there seemed to be enigmatically signified fire, by the fine flax the earth, by the blue the air, and by the purple the sea; two of them having their colors the foundation of this resemblance; but the fine flax and the purple have their own origin for that foundation, the earth producing the one, and the sea the other. This curtain had also embroidered upon it all that was mystical in the heavens, excepting that of the [twelve] signs, representing living creatures.” – The Jewish Wars 5:2, Whiston translation

The embroidered heavens on the curtain will surprise some, but this curtain represented the boundary between this world and the heavens. It was as though crossing that boundary brought the High Priest into the presence of God. It was “as though,” because the presence of God was never acknowledged to be in Herod’s Second Temple as it had been in Solomon’s Temple. The Holy of Holies no longer contained the Ark of the Covenant. Still, this was the holiest place from of old, and it was treated as such.

Aftermath of Destruction in Jerusalem, 70 A.D.

This magnificent Temple was destroyed in 70 A.D., some 40 years after the crucifixion of Jesus. That event brought changes to Israel of a magnitude unsurpassed in all its previous history. Before Jerusalem’s destruction the Temple had already become a place of murder, then hunger. When the Roman legions breached the city wall they slaughtered virtually everyone they saw, pretending not to hear calls for restraint from their commanders.

Fire consumed the Temple. Those left alive were made slaves and taken to other parts of the world. Judaism was necessarily re-invented by surviving rabbis at Tiberius. Another failed revolt followed sixty years later bringing more destruction. Not until 1948 would Israel again become a recognized nation living in its own land. (See the magnificent flooring used in the Second Temple.)

Searching for an Answer

The torn Temple curtain brings to our attention two parallel lines of thought, one from Judaism and one from Christianity, each interpreting the ruin of the nation and its Temple theologically. On this much both agree: God had brought about this devastation, not the Romans. Such a thing had already happened some six centuries earlier when Solomon’s Temple was razed by the Babylonians. The prophets said God had brought that about for the nation’s grievous, continuing sin, despite warnings.

But what were the reasons this current Temple had fallen?

From the rabbinic perspective:

“It was destroyed due to the fact that there was wanton hatred during that period. This comes to teach you that the sin of wanton hatred is equivalent to the three severe transgressions: Idol worship, forbidden sexual relations and bloodshed.” – Gemara to Yoma 9b

From the Christian perspective: Israel’s leaders had crucified the Messiah. Soon the people followed other leaders instead who incited a war that was not ordained by God. The consequence was this devastation they had brought upon themselves.

We Were Warned

Ancient people took their portents very seriously—Romans had their augurs, Mesopotamians had their sky omens, Greeks had their horoscopes.

Jewish people said God sent warnings about their Temple that went unheeded. Josephus wrote a fascinating passage about this, describing the divine portents that were witnessed at the Temple and in Jerusalem before the end (The Jewish Wars 6:5:3).

Here is a brief summary of Josephus’ Portents List:

- A new star and comet visible for a year

- Light shining around the Temple altar

- Heifer giving birth to lamb in Temple

- Massive eastern Temple door opens by itself

- Shining soldiers seen in the sky, moving through the clouds

- Priests hearing voices in the Temple, “Let us go away from here.”

- Jesus son of Ananus incessantly proclaiming the city’s approaching devastation

These seem to be fantastic legends without basis in fact. But a nova (new star) appears in Chinese lists for the year 70 A.D. That may be part of the explanation for the first portent.

Portent three may have involved a malformed, stillborn calf.

The fifth portent is the most incredible of the entire list. Josephus gives the calendar date for it, and the time of day, sunset. About a week away from Josephus’ calendar date a solar eclipse of 77% obscuration occurred at sunset in the year 67. Given the clouds present, and the phenomenon of shadow waves that accompany eclipses, plus the consequences of staring at the sun, the shining soldiers in the sky may be grounded in that eclipse.

Portent 6 brings to mind Ezekiel in the Old Testament. He beheld a vision of the Glory of the Lord departing the First Temple, leaving it desolate prior to its destruction (Ezekiel 10).

Portent four bears some similarity to the tearing of the Temple curtain. Both include a Temple doorway. No Jewish list includes the tearing of the curtain, but might that silence be explained by its coinciding with Jesus’ death? (Second Temple stones discovered beneath the Western Wall)

More Portents from the Talmud

“Forty years before the Temple was destroyed the chosen lot was not picked with the right hand, nor did the crimson stripe turn white, nor did the westernmost light burn; and the doors of the Temple’s Holy Place swung open by themselves, until Rabbi Yochanon ben Zakkai spoke saying: ‘O most Holy Place, why have you become disturbed? I know full well that your destiny will be destruction, for the prophet Zechariah ben Iddo has already spoken regarding you saying: ‘Open thy doors, O Lebanon, that the fire may devour the cedars’ (Zech. 11:1).’ – Yoma 39b

The crimson stripe referred to above was tied to the scapegoat sent away into the wilderness on the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16:21–22). It now retained its red color and never faded as before, suggesting that the nation’s sin was no longer being atoned.

Jesus’ Own Warnings

Jesus himself had foretold Jerusalem’s destruction: “For the days will come upon you, when your enemies will set up a barricade around you and surround you and hem you in on every side and tear you down to the ground, you and your children within you. And they will not leave one stone upon another in you, because you did not know the time of your visitation (Luke 19:43-44).” He wept over the city saying, “Behold, your house is forsaken” (Luke 13:32-35). He warned, when you see soldiers coming, run (Luke 21:20-22)!

And Jesus did still more. In the biblical prophetic tradition he enacted a message in the Temple. Before the first Temple fell, Ezekiel had publicly displayed Jerusalem drawn on a brick, besieged by an army. Jeremiah had publicly smashed an earthen jar representing the future of the nation, the city, and the Temple. Now Jesus “cleansed” the Temple of money changers and sacrificial animals for sale (Matthew 21:12–17, Mark 11:15–19, Luke 19:45–48, John 2:13-16).

Many New Testament scholars understand this event to include a prophetic warning, a micro-destruction pointing to a macro-destruction if no repentance followed. While not a supernatural portent like those found in Josephus and the Talmud, Jesus’ Temple action included a warning of devastation to come.

Was the tearing of the Temple curtain a portent of coming, world-changing disaster upon a nation whose leaders had killed their Messiah? Those who experienced the events of Good Friday seem to have understood it just that way (Matthew 27:51-54, Mark 15:39, Luke 23:47-48).

The tearing of the Temple curtain will remain for Christians a symbol of direct access to God, accomplished through Jesus’ death that takes away sin. But there is more to its message when placed in the context of portents. The torn curtain also tells us that failure to repent brings consequences. This is something that should prompt us to keep thinking.

TOP PHOTO: A model of Herod’s Temple in Jerusalem with curtain location inside the naos. (credit: Fred Baltz)