Summary: Hems and tassels show up in the archaeological record and their surprising significance is seen in biblical teaching.

“You shall make yourself tassels on the four corners of the garment with which you cover yourself. – Deuteronomy 22:12 (ESV)

Hems and Fringes in the Ancient World

Jesus upbraids the Pharisees in Matthew 23 for making their phylacteries1 broad and “their fringes long” (Matt. 23:5, ESV).2 To most Gentiles the statement is usually explained as a dress characteristic of the Jews to display their piety. But there is much more involved than just wide hems or tassels (fringes).

In ancient Mesopotamia, the hem of the garment made an important social statement. Documents from the city of Mari on the Euphrates (ca. 18th century BC) reveal that the hem of the garment represented the person who owned it and to cut off the hem implied an injury or denial of the person’s value.

One cuneiform letter speaks of a trustworthy person in which the author states: “since this man was trustworthy, I did not take any of his hair or the fringe of his garment.”3 Another letter, however, refers to a man who had proved dishonest, and Kibri-Dagan (the author of the letter) says: “I now hereby dispatch to my lord the fringe of his garment and a lock from his head. From that day [this] servant has been ill.”4

In the Old Babylonian period (ca. 2000-1600 BC), the bride-price (dowry) paid by the father of the bride was sewn into the hem of his daughter’s garment as part of the marriage agreement.5 In some cases, if a divorce occurred, the husband would cut off the hem of his wife’s robe.6

Further evidence of a connection of the “hem” with a person’s identity appears in declarations that diviners would deliver to the king, asserting their truthfulness and the validity of their visions. Several letters by diviners, visionaries, and cult players attest to their trustworthiness before Zimri-Lim (ruled ca. 1779-1761 BC) by including their “hair and fringe.”7 Additional connections are implied by some traditions of impressing the hem of one’s garment into soft clay to substitute for signatures8 in illiterate societies. (Learn about the discovery of the blue dye used for tassels in the era of King Solomon.)

Milgrom points out that the fringe was considered an extension of the hem9 (hence sometimes the variation of translation). The fringe could manifest itself as tassels. There is evidence that tassels were sometimes wardrobe decorations by some non-Israelite peoples. Whether these decorations were matters of fashion or conviction is unclear.

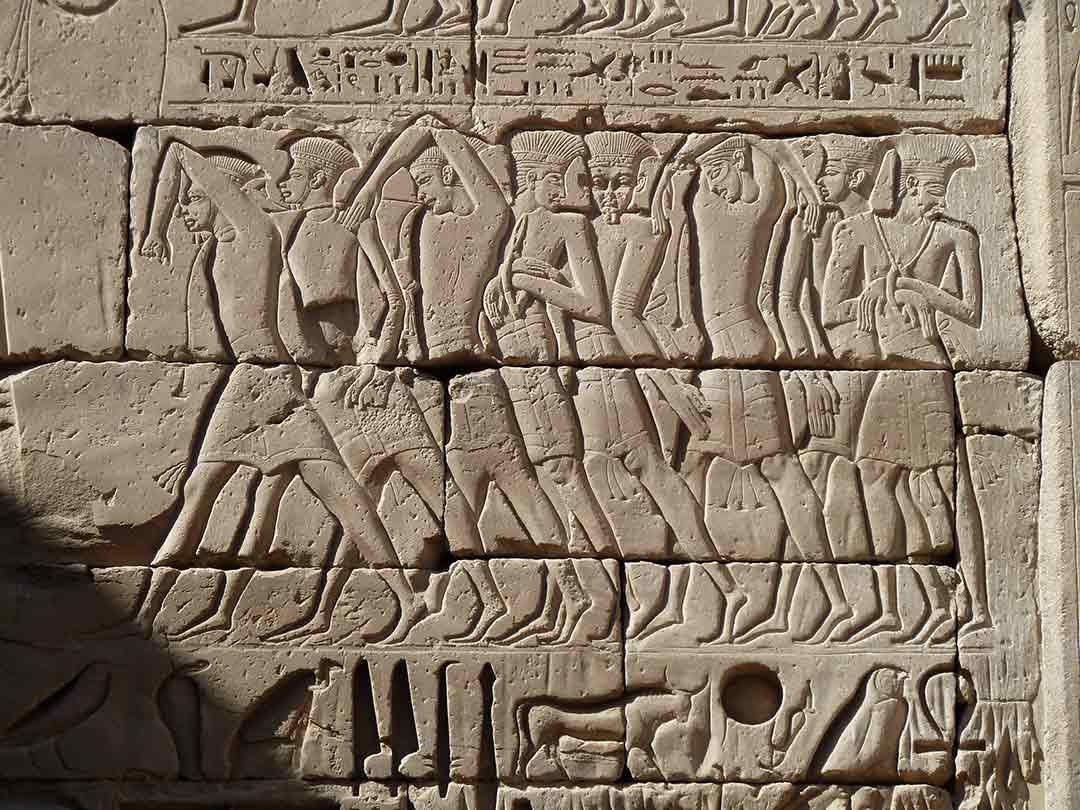

Tutankhamun (ca. 1350 BC) portrays his dominance over a Syrian captive on his ceremonial footstool and depicts him with tassels on the edge of his kilt.10 Later, Ramses III (ca. 1175 BC) commemorates his victories over the Sea Peoples and Semitic groups and one representation on his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu shows a line of captured Sea Peoples, several of whom wear tassels extending from the edge of their garment (see photo at top of article – look closely at the bottom edges of some of their garments).11

Tassels in Biblical Israel

Obviously, since other peoples had tassels (Heb: tsitsit)12 attached to their garments (perhaps as fashion statements), the presence of such for the Israelites was not unique. The LORD, however, commanded Israel to wear tassels (Deut. 22:12) and he prescribed that they include a blue cord13 as part of the garment (Num. 15:37-41). The LORD explicitly indicated that the purpose of this addition was to remind the Israelites of who they were and of the commandments that they were to obey,14 hence it became a point of cultural identity as well. (See the article on biblical plants and animals that investigates the animal related to tassels in Israel.)

The importance of the hem impinges on the narrative when David cuts off the hem of Saul’s garment after Saul ventures into the cave to relieve himself (1 Sam. 24:4-5). David and some of his men were hiding in the cave when Saul enters and they urge David to kill Saul. Instead, David surreptitiously cuts off a “corner of Saul’s robe” (v. 4).

A flood of remorse quickly overwhelms David for this disrespectful behavior against the “LORD’s anointed” (v. 6). The episode permits David to demonstrate that he meant Saul no harm by showing him the hem fragment thus proving how vulnerable Saul had been. While David’s remorse may in part have been that he had damaged Saul’s robe, greater however was that the behavior had insulted the king and Saul’s position as the LORD’s anointed. His actions were much like ours when we might think at the time that our outburst may be justified only upon later reflection to realize that our actions or words were foolish and improper.

A Biblical Warning Related to Tassels

Considering the significance of the hem and the contempt and humiliation implied in the violation of the hem, conversely, how much more significant might a person think of him/herself to display an elaborate hem or long tassels? Milgrom specifically notes: “The more important the individual, the more elaborate the embroidery of his hem. Its significance lies not in its artistry but in its symbolism as an extension of its owner’s person and authority.”15 It is to this tendency that Jesus alludes in his tirade against the Pharisees (Matt. 23:5).

They do all their deeds to be seen by others. For they make their phylacteries broad and their fringes long, and they love the place of honor at feasts and the best seats in the synagogues and greetings in the marketplaces and being called rabbi by others. – Matthew 23:5-7 (ESV)

It is likely that Jesus is actually referring to the tassels as an extension of the hem. The Greek text speaks more specifically of the hem, which likely is a synecdoche for the tassels. Jesus was not condemning the use of the tassels; he apparently observed the injunction himself. The episode of the woman’s desire to touch “the fringe of his garment” (Matt. 9:20; cf. Luke 8:44; ESV)16 almost certainly alludes to Jesus’ wearing tsitsit to conform to the Law.17 Jesus’ condemnation was using the custom as a means of self-promotion and self-aggrandizement—a behavior which most of us at times are inclined to exhibit. This should cause us all to Keep Thinking!

1 “Phylactery” is a transliteration of the Greek word phylaktērion, which Danker (1068) describes as “leather prayer band and case containing scripture passages, sometimes used as an amulet” and then defines as “prayer-band, prayer-case.” Silva (4: 626) notes that the basic meaning from which the word derives conveys the idea of “‘outpost,’ then ‘safeguard’ and ‘amulet.’” The item under consideration is what most Jews refer to as tefillin which derives from the Hebrew word “tefillah” meaning “prayer.” The reference is to the small leather boxes that contain the shema‘, (cf. Deut 6:4-9) and were worn during times of devotion and prayer.

2 The KJV reads “enlarge the borders of their garments” while the NIV (1984, 2011) offers “They make… the tassels on their garments long” (the 1978 NIV renders: “tassels of their prayer shawls…”).

3 Moran, William L. “Akkadian Letters.” Pp. 623-32 in Pritchard (p. 623).

4 Ibid., 623-24.

5 Finkelstein, J. J. “Mesopotamian Legal Documents,” Pp. 542-47 in Pritchard (p. 544).

6 Milgrom (1983: 61).

7 Moran in Pritchard, pp. 632-34 (letters m, n, p, w).

8 Milgrom (1990: 410). The Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem for several years has displayed an ancient document sealed with a person’s fingernails as his/her affirmation (photo upper left of Late Assyrian example, by DW.M, courtesy of Bible Land Museum, Jerusalem). The fingernail marks are the series of vertical parallel indentations on the left side of the upper middle register. The display also discusses using the hem of the garment, but it does not have an actual example on display.

9 Milgrom (1983: 62).

10 All the images I have seen of this footstool are copyrighted, but you may refer to Desroches-Noblecourt (50-51, 296) as well as a host of other sources.

11 Some of the reliefs at Medinet Habu portray Semitic peoples wearing tassels, but I have no photographs of those—only of the Sea Peoples.

12 In Ezekiel tsitsit refers to the lock of hair by which the LORD lifted him up in visions to Jerusalem (Ezek. 8:3). Milgrom notes that the tsitsit “resemble a lock of hair” (1990: 127) which may explain the references in the Mesopotamian literature that combine the lock of hair with the garments’ fringes (see references in Pritchard above).

13 The significance of “blue” is important. Blue was a characteristic colors associated with the priests (cf. Exo. 28:31). Perhaps this prescription for the blue cord was to remind God’s people that in a sense all of them were at least in a small way priests (cf. Exo. 19:6) and were expected to behave accordingly. In addition, the requirement of a blue cord intrinsically presented an economic impact since the production of blue, purple, violet, and red was very labor intensive, and thus expensive. I plan to address this color issue in a later discussion (—dw.m).

14 A peculiar story appears in the Babylonian Talmud (Menachot 44a) in which a fellow who was meticulous in his observance of the tsitsit went to a prostitute. As he approached her, the “four ritual fringes came and slapped him on his face.” This prompted him to remember his moral responsibilities and he refused to follow through with his plans. In addition, the prostitute was intrigued by his repentance and eventually converted as well! (cf. sefaria…)

15 Milgrom (1990: 410).

16 The Greek word in Matthew is kraspedon which Danker defines as “edge, border, hem” (564). Danker, however, notes that tsitsit is also a probable meaning. Certainly corroborating this interpretation is the fact that kraspedon is the word that appears in the Septuagint of both Deuteronomy and Numbers to prescribe the tassels.

17 See Albright and Mann (111); Lewis (139); and Hagner (249).

Bibliography:

Albright, W. F. and C. S. Mann. Matthew. Anchor Bible 26. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971.

Danker, Frederick William (rev. and ed.). A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other Early Christian Literature, 3d ed. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2000.

Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane. Tutankhamen: Life and Death of a Pharaoh. London: George Rainbird, 1963.

Hagner, Donald A. Matthew 1-13. Word Biblical Commentary 33a. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2000.

Lewis, Jack P. The Gospel According to Matthew, Pt. 1. Living Word Commentary. Austin, TX: Sweet, 1976.

Milgrom, Jacob. “Of Hems and Tassels.” Biblical Archaeology Review 9.3 (1983): 61-65.

__________. Numbers. JPS Torah Commentary. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990.

Pritchard, James B. (ed.). Ancient Near Eastern Texts, 3d ed. with supplement. Princeton: Princeton University, 1969.

Silva, Moisés (ed.). New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis, vol. 4. 2d ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2014.

TOP PHOTO: A line of captured Sea Peoples from a relief commemorating the victory of Ramses III on his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu. Look closely to see tassels on the bottom edges of some of their garments. (© Dale Manor)

NOTE: Not every view expressed by scholars contributing Thinker articles necessarily reflects the views of Patterns of Evidence. We include perspectives from various sides of debates on biblical matters so that readers can become familiar with the different arguments involved. – Keep Thinking!