Summary: New evidence of an inkwell and reassessments of past evidence of messages from the Judean fort of Arad reveal that reading and writing was not as rare in ancient Israel and Judah as many scholars had previously believed.

And these words that I command you today shall be on your heart. You shall teach them diligently to your children … You shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates. – Deut 6:6-9 (ESV)

Literacy, Judah and the Bible

Last week we profiled new archaeological evidence, that was a surprise to many, showing that Judah was a very robust centralized kingdom in the 7th century BC, supporting the biblical account of conditions at this time. Now, new evidence is coming forward indicating that literacy rates in different periods were not as low as previously thought.

The question of literacy rates in ancient Israel has long been debated by archaeologists. The Bible paints a picture that seems to indicate literacy was at least somewhat widespread – even among common people. But because of the lack of evidence (written documents) many scholars hold the view that literacy was rare – perhaps confined to a very small group of priests and royal scribes. This skepticism not only affects views about the accuracy of the Bible, but also opinions about when its books could have been written or compiled.

An Inkwell from 1st Century Judea

The first piece of evidence comes from the Khirbet Brakhot excavation site in Gush Etzion, just south of Bethlehem. An intact inkwell was discovered inside the remains of a large Second Temple period building. The Second Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed in AD 70, so this dates the find to the first part of the 1st century.

The inkwell has a thick clay cylinder with a rounded handle and flat base. A narrow opening on top with an inward-sloping rim received the ink and pen. According to the archaeologists, discoveries of inkwells from this period have so far been rare. Similar finds have come from only a dozen other sites across the country.

Due to the COVID pandemic only a few excavations are currently operating in Israel, mainly by Israelis. This one is conducted by the Archeology Command Unit of the Israeli Civil Administration in Judea the West Bank, in collaboration with Herzog College.

The 2,000-year-old inkwell is believed to have belonged to a writer or merchant and bolsters the view that literacy was more widespread than just among administrators in the Jewish population at this time. The New Testament also portrays writing in the 1st century as more common, with Jesus telling a parable that assumes debtors to a manager would be able to read and adjust their bills of debt (Luke 16:1-9), and the apostles (most of whom were fisherman) writing letters to the numerous new churches with the assumption that they could be read.

And when he wished to cross to Achaia, the brothers encouraged him and wrote to the disciples [there] to welcome him… – Acts 18:21 (ESV)

7th Century BC Messages Written by Soldiers of Judah at Arad

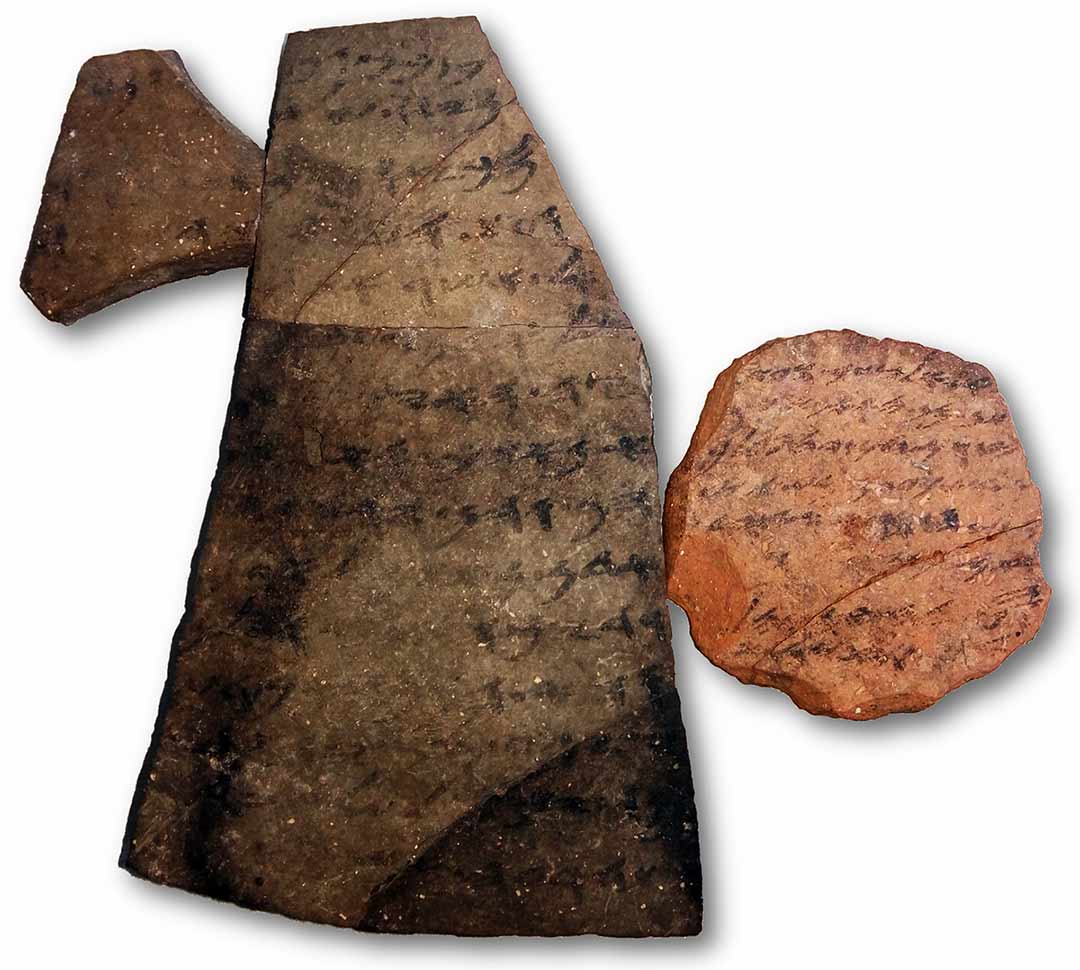

It is generally accepted that there was more literacy in 1st century Judea than in Judah during the time of the biblical kings (prior to 586 BC). Now however, new archaeological findings come from a reassessment of a set ostraca (clay potsherds with ink inscriptions) found decades ago at the site of Arad, a well-preserved fortress near the southern border of Judah.

Thinker Updates wrote about the initial findings in 2016 with the implication that the Bible could have been written earlier than many scholars believed. Around 600 BC, the fort at Arad is believed to have been occupied by a contingent of 20-30 soldiers. This was the period just before Jerusalem and the Kingdom of Judah were destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians. In the remains of the fort over 100 ostraca were found written in Hebrew with a variety of different messages.

Remarkably, one of the inscriptions mentions the ‘King of Judah’ and another the ‘House of YHWH,’ possibly referring to the Temple in Jerusalem.

When 18 of the ostraca with the longest messages were initially studied using algorithmic analysis, it was found that between 4-7 different individuals were responsible for writing the 18 messages. This was a surprising result, but the best was yet to come.

Modern Forensics helps crack the Biblical Mystery

Researchers from multiple disciplines at Tel Aviv University have now teamed up with a forensics handwriting expert to reexamine the writings from Arad. In an article recently published in the Public Library of Science (PLoS One) their ground-breaking conclusion was that “…according to the forensic analysis, the number of independent writers within the Arad corpus is at least 12 (!).”

The handwriting analysis of Yana Gerber was a key factor in the new study. She served for 27 years in the police’s forged documents unit and also happens to have a degree in classical archaeology and ancient Greek. “This study was very exciting, perhaps the most exciting in my professional career,” said Gerber. “These are ancient Hebrew inscriptions … utilizing an alphabet that was previously unfamiliar to me.”

“I delved into the microscopic details of these inscriptions written by people from the First Temple period, from routine issues such as orders concerning the movement of soldiers and the supply of wine, oil and flour, through correspondence with neighboring fortresses, to orders that reached the Tel Arad fortress from the high ranks of the Judahite military system. I had the feeling that the time stood still and there was no gap of 2,600 years between the writers … and ourselves,” she continued.

Gerber explained that “Handwriting is made up of unconscious habit patterns …unique to each person and no two people write exactly alike.” She examined the microscopic details of each inscription down to the spacing between each letter, their proportions, slant, etc.

“It is also assumed that repetitions of the same text or characters by the same writer are not exactly identical and one can define a range of natural handwriting variations specific to each one. Thus, the forensic handwriting analysis aims at tracking features corresponding to specific individuals and concluding whether a single or rather different authors wrote the given documents,” said Gerber.

“We were in for a big surprise: Yana identified more authors than our algorithms did,” said Dr. Arie Shaus of Tel Aviv University who conducted the study. “We can conclude that there was a high level of literacy throughout the entire kingdom,” Shaus said, adding the fact that so many soldiers were literate points to “the existence of an appropriate educational system in Judah at the end of the First Temple period.”

“If in a remote place like Tel Arad there was, over a short period of time, a minimum of 12 authors of 18 inscriptions, out of the population of Judah which is estimated to have been no more than 120,000 people, it means that literacy was not the exclusive domain of a handful of royal scribes in Jerusalem,” said Tel Aviv archeologist Prof. Israel Finkelstein. (See the Update on the discovery of cannabis use from an altar at Arad)

The researchers stress that when assessing the prevalence of literacy in Judah, this evidence should be considered together with ostraca unearthed at other outposts on the southern periphery of Judah (marked on the map). At one site 34 inscriptions were discovered, including a piece of wisdom literature reflecting a high degree of literacy. At another site the officer writing a message is seemingly offended by the suggestion that he is assisted by a scribe!

What About Literacy in Early Israel and the Writing of the Bible?

This evidence impacts scholars’ views of when the earliest books of the Bible could have been written (or compiled), because they believe such complex works were unlikely to have been composed until literacy was fairly widespread. However, this thinking seems unwarranted, since all the ancient Egyptian inscriptions and documents in hieroglyphics were written when the literacy rate was very small.

The Bible does seem to imply that literacy was somewhat widespread among the Israelites in the time from Moses to the first kings of Israel. For example, Moses instructed the heads of Israelite households to write the commandments on their doorposts (Deut. 6:6-9) and allowed men to write certificates of divorce (Deut. 24:1-3). Men from each tribe wrote descriptions of the land of Canaan for Joshua (Josh 18:8-9).

A young man captured in the field by the judge Gideon wrote down for him the officials and elders of Succoth, seventy-seven men (Judges 8:14). King David wrote messages to his military commanders (2 Sam 11:14-15). Jehu wrote letters and sent them to the rulers of the city, to the elders, and to the guardians of the 70 sons of Ahab (2 Kings 10:1, 6) and Queen Jezebel wrote letters in Ahab’s name to the elders and the leaders who lived with Naboth in his city (1 Kings 21:8-9).

Are these biblical accounts doubtful simply because we have no direct physical evidence of these writings? It should not be expected that physical remains of these documents would survive in Israel’s climate for 3,000 years since the preferred medium for writing, animal hide, decays. Storage rooms in Judah from the era of 700-600 BC have been found containing numerous bullae or clay seals that once tied together manuscripts that have completely rotted away. The reason the brief messages survived at Arad is because potsherds were freely available, and the arid climate of the Negev helped preserve the ink.

As covered in the film The Moses Controversy, there are inscriptions from the times of the judges and early kings in Israel that are typically brief and unpolished graffiti on clay or stone that are evidently not the product of scribes. This suggests that writing was widespread. But these have been dubbed as “Canaanite” by most scholars and not connected to the Israelites.

The finds of an inkwell and ostraca from low level soldiers on the frontier of Judah excite the imagination for what life was like in biblical times. It seems the emphasis on education and literacy among the biblical faiths goes back to very ancient times. The Bible does not say what the literacy rate was in ancient Israel, but it does indicate that it was not rare. Now evidence shows that in ancient Israel literacy was not the exclusive domain of a handful of royal scribes, so there is no need to doubt the biblical accounts on these matters. As was the case in last week’s Update on architecture, this emphasis on writing and education came centuries prior to the classical Greeks. We look forward to hearing about more discoveries in the future that will continue to impact this subject. – KEEP THINKING!

TOP PHOTO: Examples of two Hebrew ostraca from Arad. (credit: Yana Gerber, Israel Antiquities Authority)