SUMMARY: The Bible was written in three languages, on three continents, over 1500 years. Here, we explore how.

See, I have taught you statutes and rules, as the LORD my God commanded me, that you should do them in the land that you are entering to take possession of it. Keep them and do them, for that will be your wisdom and your understanding in the sight of the peoples, who, when they hear all these statutes, will say, ‘Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people.’ – Deuteronomy 4:5-7 (ESV)

In our previous study, we considered instructional factors that challenged biblical educators and that give rise to questions like: What is the connection between Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek? What about the language(s) spoken by Jesus and the Apostles? Did they preach in the same language in which they read the Torah, or in the language of the hearing audience? And what language was that? Perhaps you have wondered, “Why did the Jewish authors of the New Testament produce it in Greek?” Or, “Since the Roman Empire was in control of Judea during the time of Christ, was Latin a factor?” These questions are fascinating, and are related to the interplay of nations, languages, and God’s sovereignty.

Nations, Languages, and the Torah

Throughout the history of Israel, geo-politics has played an ongoing role in the formation and survival of this unique nation. The Torah expressed in advance that this would be the case, that it would be challenging, and that it would be part of the very spiritual witness of the nation. At times, interaction with other nations impacted the very language(s) of Israel and thus contributed to the challenge of spiritual education.

This is why the corpus of the Bible was written in three languages, over 1500 years, and on three continents. In a sense, this is a linguistic record of God’s work to preserve and restore His people. Several places in the text of Scripture provide a snapshot of some of these encounters and provide fascinating glimpses into how nations and languages often converged.

Assyria and Linguistic Diplomacy

In 701 BC, in the 24th year of King Hezekiah of Judah, the Assyrian king Sennacherib invaded Judah and besieged Jerusalem. In the process of negotiating the terms of surrender, the Assyrian representatives engaged in a bit of linguistic diplomacy. They intentionally addressed Hezekiah’s team in Hebrew, instead of Aramaic, and while in public. This means that they strategically spoke in the language of the people, while in the hearing of the people, in order to potentially influence the people. (Unique evidence of King Hezekiah has been discovered in Jerusalem.)

The goal of the Assyrian representatives was to maximize the effect of their persuasion by destabilizing the Judeans’ confidence in their leaders. Sennacherib was already in the process of attacking Lachish, and was having success. So, the impact of the tactic was not lost on the Judean officials. They knew the people would be terrified, and so they feebly responded with a plea that the Assyrians address them in Aramaic. They begged,

Please speak to your servants in Aramaic, for we understand it. Do not speak to us in the language of Judah within the hearing of the people who are on the wall. – 2 Ki. 18:26 (ESV; see also Isaiah 36:11)

The Assyrian envoy immediately recognized the request as confirmation of the tactic’s effectiveness. So rather than comply, the delegation was only emboldened. The text records that in response to the Judean leaders’ plea, the negotiator only ramped up his rhetoric and launched into an extended diatribe against King Hezekiah. But not only did they malign the king, they included a blasphemous tirade directed toward Israel’s God. This was, again, strategically conducted in Hebrew and in the hearing of the people on the wall.

However, this libel directed toward God was a colossal mistake that would ultimately prove fatal. The Assyrians may have successfully destroyed Lachish, but in their attack of Israel’s God, they crossed a line. After some additional diplomatic back-and-forth, God brought about a monumental judgment on the Assyrian forces that permanently removed them from the Israelite landscape. According to 2 Kings 19, the LORD devastated the army of the Mesopotamian Empire in a single night. It states,

And that night the angel of the LORD went out and struck down 185,000 in the camp of the Assyrians. And when people arose early in the morning, behold, these were all dead bodies. Then Sennacherib king of Assyria departed and went home and lived at Nineveh. And as he was worshiping in the house of Nisroch his god, Adrammelech and Sharezer, his sons, struck him down with the sword and escaped into the land of Ararat. And Esarhaddon his son reigned in his place. – 2 Ki. 19:35-37 (ESV)

Sennacherib never returned to Judah. Instead he went home and constructed the Lachish reliefs which bragged of his defeat of that single Judean city. Like the maniacal monarch he was, he emphasized his success while making no mention of how Jerusalem somehow managed to survive in the face of so powerful an army. So, he created his trophies and hung them in his famed “Palace Without Rival” at Nineveh where they remained until being removed to their current home in the British Museum. (see smashed idols as evidence of Hezekiah’s reforms)

Sennacherib managed to hang on for over a decade after his defeat. However, his final and inglorious demise came in the form of murder at the hands of his patricidal sons. After decades of harassment, the Assyrian king had been judged to such an extent that his army was never again able to return to Judah. Sennacherib may have been out of the picture, but that was not the end of Mesopotamian threats to Judah. Nine decades later, a new threat emerged, and this threat finally ended Assyrian primacy. (Were the Hanging Gardens of Babylon actually made by Sennacherib?)

Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylon Factor

In 627 BC, the last great Assyrian King, known as Ashurbanipal, died under unclear circumstances. With his passing, Assyrian primacy ended and a new threat emerged. This began the next year when in 626 BC Nabopolassar, a former Assyrian official rebelled and established himself as the founder and king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

Nabopolassar immediately began uniting the whole region under his control. Then, in 612 BC he threw off Assyrian oppression in a coalition of nations, sacked Nineveh, and ended Assyrian hegemony. In Assyria’s demise, Babylonian dominance was secured. This geo-political restructuring had a lasting effect on the Israelite remnant and ultimately impacted the language of the biblical canon. Centuries later, it was still visible in the language of Second Temple Jews and even influenced what Jesus said on at least some occasions.

Nebuchadnezzar succeeded Nabopolassar and became the most powerful and longest ruling king of the new Babylonian Empire. His impact on Judah was legendary and uniquely transformative. His version of the story is told in a record known as the Jerusalem Chronicle. In it he describes his ascension to the throne and capture of Jerusalem among other things. (See the unlikely prediction made by Isaiah that Assyria would fall to Babylon, confirmed by a new find.)

As recorded in 2 Kings 24 and 25, Nebuchadnezzar conquered the Southern Kingdom of Judah through a series of campaigns. The year of 586 BC is often cited as the main reference point for what became a 7 decade-long sojourn of the Judeans in Babylon. It was during this period that the widespread adoption of the Aramaic language by the Jews occurred.

Akkadian had been the earlier language of Mesopotamian civilization and was in vogue from ca. 2500-600 BC. But it had begun to decline around the 8th century BC and so was essentially replaced by Aramaic by the time of the Judean captivity (it managed to linger on for a while with the last known example dating to the 1st century of the Christian era). Since the biblical prophet Daniel was a young exile that rose to prominence in the Babylonian government, it only makes sense that he would have been literate in both Hebrew and Aramaic.

This bilingual capacity even shows up in his book where he writes in alternating Hebrew and Aramaic. Daniel begins by using Hebrew to tell his personal story but shifts to Aramaic in Chapter 2:4 when he quotes the words of the Chaldeans. He continues in Aramaic as long as the narrative stays focused on incidents related to the Babylonian court. In 7:28, Daniel shifts back to Hebrew at a point where the narrative frame transitions back to personal matters.

Then the Chaldeans said to the king in Aramaic, “O king, live forever! Tell your servants the dream, and we will show the interpretation.” – Daniel 2:4 (ESV)

Cyrus and the Persian Era

In 538 BC, Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon and established the Achaemenid Empire (also known as the First Persian Empire), which at the time was the largest empire the world had ever seen. However, this had no effect on the language of the Hebrews. Cyrus quickly issued the Edict of Restoration (Ezra 1:1-4; 2 Chron 36:22-23), which allowed the repatriation of various peoples conquered by the Babylonians to return home (his policy of repatriation is documented in the Cyrus Cylinder discovered in 1879).

When the Jews returned, they took Aramaic back home with them. However, the language was already so entrenched in the land, that when the Samaritans complained to Artaxerxes about the rebuilding of the temple, they composed their letter in Aramaic. Once at court, though, it was translated for the king into his preferred language.

And in the reign of Ahasuerus, in the beginning of his reign, they wrote an accusation against the inhabitants of Judah and Jerusalem. In the days of Artaxerxes, Bishlam and Mithredath and Tabeel and the rest of their associates wrote to Artaxerxes king of Persia. The letter was written in Aramaic and translated. – Ezra 4:6-7 (ESV)

These realities illustrate how the shift from Hebrew to Aramaic had become irreversible and resulted in the rise of the Aramaic Targum (described in Part 1). They also provide background to the challenging dynamics experienced by Ezra. However, the situation was not static, and with the rise of Greek culture, another language would be thrown into the mix.

It’s All Greek to Me!

By the fourth century BC, the Greek general Alexander the Great conquered Persian King Darius III and the entire Achaemenid Empire with him. In his quest to conquer the “ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea,” he spread Greek influence across a huge geographic area including the Mediterranean coastal region, the Middle East, Northeast Africa, and Southwest Asia. Throughout these areas, a new admixture of culture occurred creating a Greek-local flavor fusion referred to as “Hellenization.” The term is derived from the ancient Greek term for “Greece,” which was “Hellas” (Ἑλλάς, Ellás). In this way, those who were heavily influenced by Greek culture have historically been referred to as “hellenized.”

Part of this new reality was the spread of a new lingua franca, or common language, throughout the Hellenized world. This new common language was known as Koine (Common) Greek. The geographic dispersion of this language and culture was so encompassing, that it was still discernible as late as the 20th century in some communities.

The domination of Alexander included Egypt, which became a Hellenized Kingdom under the control of his Greek General Ptolemy 1 Soter at Alexander’s death. His son Ptolemy II Philadelphus succeeded him as Pharaoh, and was noted for his love of culture, especially literary culture. It was this man who founded the Great Library of Alexandria and commissioned a translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek known as the Septuagint, or LXX.

One of the impacts of this translation is that it became heavily utilized by Hellenized Jews and Christians including those who would go on to author the New Testament (NT). Additionally, these factors ensured that the audience of the NT would have a Bible written in a common language accessible at an unprecedented scale. Even though the Latin-speaking Roman Empire was in control of the East Mediterranean during the time of Christ and the Apostles, Greek had been the common language since the time of Alexander the Great.

Greek was so pervasive, that it remained the language of the non-Roman populace and of much literature during the 1st century. The end result was that many cities in the Roman Empire, including the city of Rome, were completely bilingual. This reality is why the New Testament was written in Greek, with a few quotes from Jesus in Aramaic and with a smattering of transliterated Latin words (i.e. Latin words written in Greek characters).

The area in the vicinity of Jerusalem was very cosmopolitan and inhabited by Hebrews (primarily Aramaic speakers), Romans (primarily Latin speakers), and a culturally mixed population that spoke primarily Greek. As a result, even the sign nailed to Jesus’ cross reflects the multi-linguistic element of the area. The Gospels express that nailed to Jesus’ cross was a sign written in three languages, namely Hebrew, Greek and Latin. The sign read, “This is the King of the Jews” (cf. Luke 22:38) in all three languages so everyone who passed by could read it. Highly educated Jews like the Apostle Paul would have been completely fluent in at least 3 if not 4 languages.

In the end, the early Christians took advantage of the widespread use of the Greek language as well as the Roman road system to spread the Gospel and proliferate copies of the NT. Evidence of this fact is clear from the ancient copies of the NT that have been discovered. For example, the New Testament papyrus manuscript known as P46 dates to about AD 200 and originally contained 10 of Paul’s epistles plus Hebrews. It provides confirmation for the form of the Greek Bible in Egypt in the second century prior to the Diocletian persecution.

Similarly, P52, also known as St. John’s Gospel, is the earliest manuscript of any portion of the New Testament. According to Bruce Metzger,

“P52 proves the existence and use of the Fourth Gospel during the first half of the second century in a provincial town along the Nile, far removed from its traditional place of composition (Ephesus in Asia Minor). Had this little fragment been known during the middle of the past century, that school of New Testament criticism which was inspired by the brilliant Tübingen professor, Ferdinand Christian Baur, could not have argued that the Fourth Gospel was not composed until about the year AD160.” (Bruce Metzger, The Text of the New Testament – Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1992, ISBN: 9780195161229)

The Greek papyrus manuscript known as P66 was discovered in Egypt in 1952. It is a remarkably well preserved and near complete codex of the Gospel of John. The first 26 pages are intact, and even some of the original stitching remains. The traditional dating has placed its origin to be between AD 100 and 200.

The reason for such a strong NT tradition is directly connected with the socio-linguistic factors at the time of Christ and the founding of the Church. The New Testament (finished by ca. AD 100) was written completely in Greek while later church history and theology is recorded in Latin. These details are part of the Christian story. They factor into how early Christians received the Bible. And they are worth much reflection. To that end, KEEP THINKING!

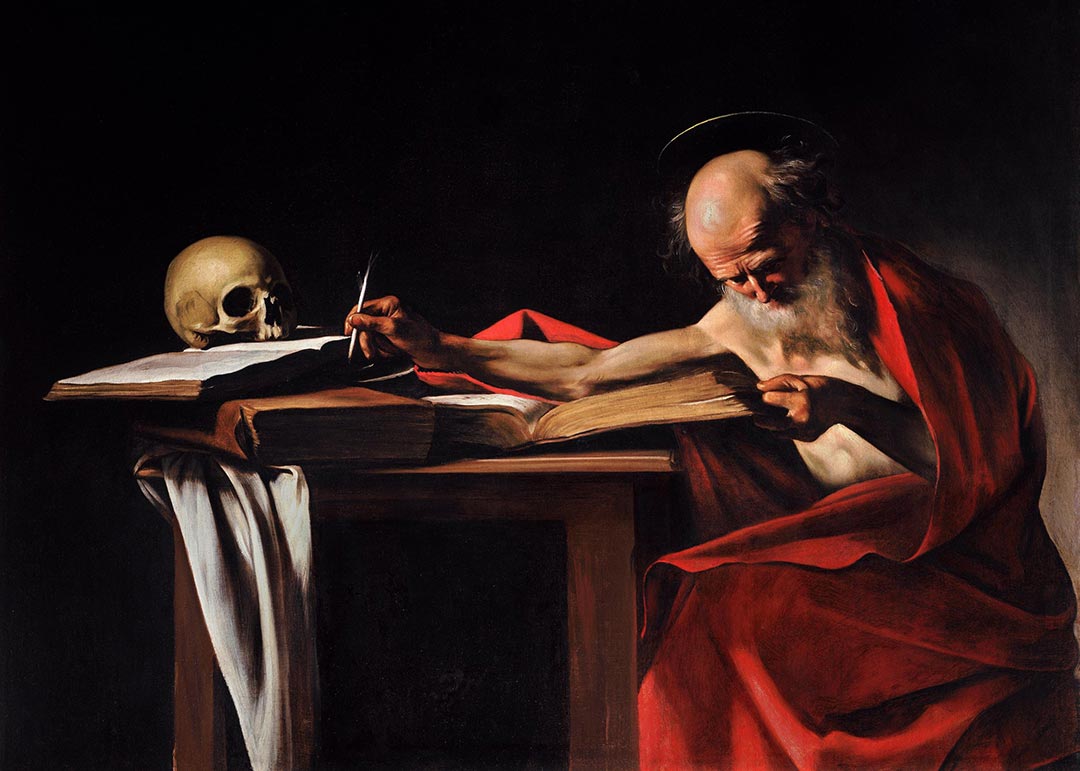

TOP PHOTO: Saint Jerome in his study by Caravaggio, ca. 1605. (public domain, wikimedia commons)

NOTE: Not every view expressed by scholars contributing Thinker articles necessarily reflects the views of Patterns of Evidence. We include perspectives from various sides of debates on biblical matters so that readers can become familiar with the different arguments involved. – Keep Thinking!